Essentially, Daly’s argument is that homicide rates are strongly related to Darwinistic, or what he calls “ecological and economic,” reasons. He showed some very compelling data, which I’ll post if I can get the slides.

A summary of his findings:

Most killers are (young) males

Across countries, most killers are men. These men tend to kill other men, especially unrelated men. The main exceptions are countries where homicide is rare, the effect in these cases being that as male-on-male homicides decline, other types of homicides – which stay relatively constant – become more prominent. Male-on-unrelated-male killings make up the great majority of homicides and are also the most variable component of the homicide rate. Women, when they kill, do tend to kill other women, but relative to men, they are much less likely to commit homicides.

Daly believes that the reasons are tied to biology. Historically, compared to women, men had a higher likelihood of dying childless, higher maximum fitness (and higher variability in fitness), and greater association between social rank and their ability to reproduce. Together, this resulted in more same-sex competition and less deterrence by danger.

This argument is supported by the age graphs of men who kill unrelated men. Across nations, they look nearly identical, sharp almost-vertical cliffs between the ages of 14 and 24 with steep drop-offs after that age and descending throughout the average male life. Most killers are young males.

Men kill each other for competitive reasons

The most significant reason why men kill each other is social competition, in the form of a response to status challenge, rivalry over a women, or disrespect (“dissing”).

The next most significant motive is material competition, in the form of robbery or business (e.g. drug) rivalry.

Risk factors for homicide

Daly believes that killers tend to be men who are so undeterred by danger that they’ll risk their lives in competitive contests. In the words of Bob Dylan,“when you got nothin’, you got nothin’ to lose.”

Unemployment is a sizable risk factor for being the perpetrator of homicide. Interestingly, unemployment is also a risk factor for being the victim of homicide, a possible explanation being that people tend to interact with others like them.

Being unmarried is another risk factor. That’s specifically not married, meaning that even if you’re in a serious relationship, you’re still in the risky pool. The rate of homicide for men who become divorced and widowed returns to the unmarried rate.

Generally, the more inequitable men’s access to “resources” (which apparently include child-bearing wives), the more dangerous disenfranchised men become.

A bit of math

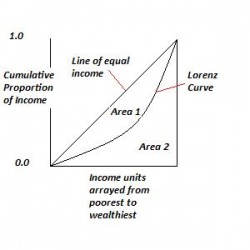

Just in case you were wondering, inequality is calculated through the Gini coefficient of income inequality, which seems to be the gold standard for these things.

The equation is as follows:

Gini coefficient of income inequality = Area 1 / (Area 1 + Area2)

Where: the y-axis is the cumulative proportion of income from 0 to 1 and the x-axis is income units (households) arrayed from poorest to wealthiest. The line of perfect equality would be the straight y = x line, meaning that every household’s income adds to the cumulative total some constant amount. The sum total of the area of the triangle Area 1 + Area 2 is the denominator. However, perfect equality never happening in the “wild,” the Lorenz curve represents the reality of the distribution. The area between the line of perfect equality and the Lorenz curve becomes the numerator.

So you might be wondering, is it really an issue of inequality and status, or is it simply poverty and its ills at work? (This is what I was thinking.)

The data is quite compelling. The number-one predictor of homicide rates across 50 US states is income inequality (with an r = 0.72, for those of you who care about these things). Average income is not a predictor at all of homicide rates (r = -0.17). [By the way, if you would like to avoid being the victim of homicide, don’t visit Louisiana and Mississippi. Go to North Dakota instead... though death by boredom is probably not that much more fun.]

But isn’t there some correlation between poverty and inequality? Aren’t poor states the most unequal?

There is some moderate correlation between poverty and inequality, but there's no reason it has to be so. Daly, who happens to be Canadian, then looked at Canadian provinces, where the poor provinces are the most equitable and the rich provinces are the most inequitable. Here, income inequality was still the main predictor of homicide rates (r = 0.82) across 10 provinces. Income was not at all a good predictor of the homicide rate; in fact, the lowest income provinces had the least homicides, arguably because they are the most equal.

When you combine Canada and US data, they fall into line -- though Canada generally has lower inequality and lower homicide rates, its worst provinces about on par with the best US states.

Culture doesn't seem to be a major factor

Some might ask, well, how about culture? Some cultures are just generally more war-like, even barbaric. You would expect to see a higher homicide rate there. Haven’t cultural transmission dynamics broken the links between violence and the economic / ecological basis?

Well, let’s look at the notoriously gun-toting U.S. South and their “culture of honor”.

Southerners tend to:

- Oppose gun control more

- Favor death penalty more

- Be more supportive of military spend

- Approve of corporal punishment more

- Be more lenient to wife-beaters

- Show more sympathy to pleas of “provocation”

You would perhaps expect homicides in the South to be greater than the North, due, at least in part, to culture. However, when you plot the graph, “Southern” tendency to homicide actually becomes about income inequality (r = 0.725).

Daly believes that behaviors of low-status individuals are adaptive and economic, not just pathological. Cultures have a degree of inertia but they do change. Younger generations will reject the attitudes and values of their elders if, and only if, it makes sense. Homicide rates in the US, for instance, dropped 40 points (from 100) between 1990 and the present, far less than one generation. Dramatic change can happen relatively fast.

Some counterarguments…and their counter-counters

Nisbett (whose conclusion was that higher homicides in the South was due to path-dependent culture transmission that continued after the initial conditions no longer existed) objected to the inclusion of both black and white men in Daly’s analysis. After all, there was so much complexity due to past slavery, current race relations and disparate income levels. However, when Daly restricted the analysis to white men, income inequality was still a strong predictor of homicides (r = 0.68), while income was not a predictor at all.

Another counterargument is that there has recently been a general upward monotonic trend in inequality in both the US and UK. At the same time, homicide rates in both nations have been on the decline. What gives?

Daly suggests that this is due to a demographic shift away from young males in both these nations with the aging population. As you might recall, killers tend to be young males. After the Gini coefficient for income inequality, the proportion of 15-34 year old men in the population is the best explanation for the residual variance. If you take a look at nations with higher income inequality, the decline in homicide rate due to changing demographics is not as steep as you would expect. Inequality essentially puts brakes on the some of the benefits of the demographic shift.

This is direct contradiction with Steven Levitt, who dismisses demographics as one of the reasons behind the decline in crime and focuses on other factors, including and notoriously, abortion. Daly suggested that a reduction in the number of young males should result in a more-than-linear drop in homicide rate. If you do the thought experiment of imagining a city where people are roaming around like little Brownian particles, and two men of a certain age need to bump into each other to result in a homicide, you would expect if you removed a sizable number of young males that dyadic interactions would be reduced more than linearly with the number of men removed.

There also may be cohort effects, meaning that the generation into which you are born has an impact on your later success in life (on average). For instance, studies have shown that large cohort size (such as the Boomer generation) affect the availability of work opportunity, the level of competitive intensity, and the general amount of adversity experienced by the average person within that cohort. It is plausible that young males in recent times, who were born into a smaller and therefore less competitive cohort, would generally commit homicides less as a group – especially when you consider that men tend to commit homicides for competitive reasons. In Japan, when you look at the total homicide data over age ranges, you would see the same peak for young males as other nations but a flatter, more gradual drop-off. But when you look at specific generations, you see a much sharper effect in all cohorts but which is more pronounced and taller (i.e. more homicides) for older pre-WWII generations. When you combine cohorts, the now older, more competitive cohorts create a deceptively flatter chart. In general, cohort effects offer another explanation for the recent divergence in homicide rates and income inequality.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed